In March of 2015, The Guardian published a piece on Prince’s vault, begun by his former sound engineer Susan Rogers before his Purple Rain superstardom: “It’s an actual bank vault, with a thick door,” she said, “in the basement of Paisley Park. When I left in 87, it was nearly full.” That was 30 years ago. Composer and Prince orchestrator Brent Fischer speculated that “over 70% of the music we’ve worked on for Prince is yet to come out.” Already able to release “in a decade what most musicians couldn’t put out in a lifetime,” Prince stored in his vaults enough to reveal him as thrice the prolific genius we knew in life.

Now that Prince has departed, the vault has been finally been opened. What’s in it? Speculation, rumor, and hoaxes abound; we could see a posthumous album a year for the next century. As they trickle out we’ll likely see more conventional, less Prince-like releasing strategies, now that he is no longer personally in control of his output. This will surely make it easier on his fans, but will also strip the music of much of its curious mystique. “A streaming skeptic before it was fashionable,” writes August Brown at the L.A. Times, and “a born futurist,” Prince excelled at “creating new distribution systems under his purview.” As an early adopter of web technology, he began giving away and selling his music and merchandise online as early as 1996, when he created his first official website, “The Dawn” (above).

Prince’s web debut happened in the midst of his pitched battle with Warner Brothers, and three years after he changed his name to the “Love Symbol.” Browsing through the history of his internet strategies allows us to see how his personalized distribution approaches and online identities evolved over the next two decades as he regained full creative independence. We can easily survey that history all in one place now, thanks to the Prince Online Museum, an archive of 16 of Prince’s various websites, each one with its own profile written in Prince’s distinctive idiom, with “testimonials from the people who were involved in creating and running them for Prince,” writes The New York Times, and “links as well as screen shots and videos” of each site, none of them currently active.

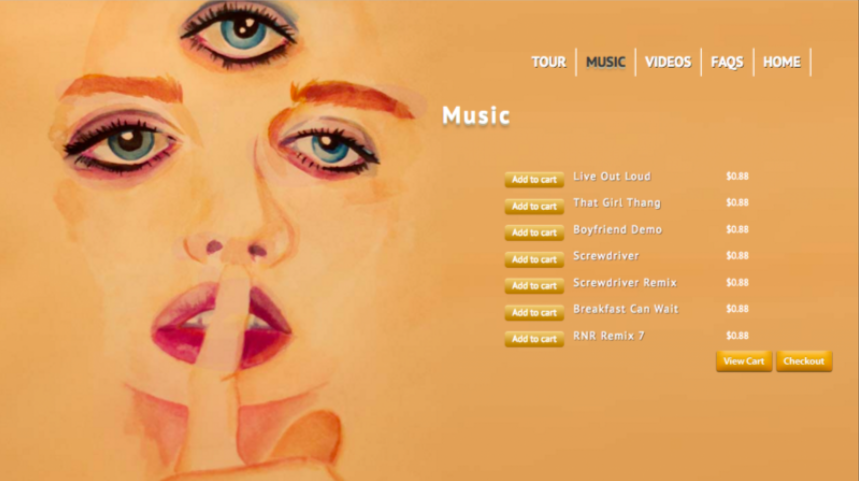

There’s even a precursor to Prince’s online world, Prince Interactive, a 1994 CD-Rom “coupled with Prince’s underground film, The Beautiful Experience.” This early attempt makes clear that “Prince was fascinated and excited by the possibilities of connecting directly 2 his audience through their computers. It would be several years until that became a reality 4 him, but the idea started here.” (See a slow video walk-through of the CD-Rom above). After 1996’s “The Dawn” came the first official online retail store, “1–800-NewFunk,” and an online lyric book, “Crystal Ball Online.” Successive sites each had a distinctive focus: on Prince’s charitable foundation with “Love 4 One Another”; on various iterations of his “NPG Music Club,” an “online distribution hub”—including the “virtual estate” of the 2003 iteration (see picture further up); and on rebranding efforts like “3121.com.”

One of the most striking of all of the various sites, “Lotusflow3r” (top) contained “vibrant 3D imagery and animation connected 2 the music” and design of the 3‑CD album set of the same name from 2009. The last entry in the archive, the “3rdEyeGirl” site from 2013, was created for Prince’s new band and “was another example of choosing 2 bypass traditional channels and go his own way.” Each of these site profiles act as “snapshots in time to experience the Web sites just like when they were active,” writes Prince Online Museum director Sam Jennings. They also showcase “his fierce independence” and desire “to connect directly with his audience without any middleman.”

You can explore the Prince Online Museum here.

Related Content:

The Life of Prince in a 24-Page Comic Book: A New Release

Prince Plays Unplugged and Wraps the Crowd Around His Little Finger (2004)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply